This year’s FofoFocus Biennial, a month-long celebration of photography spanning Cincinnatti and the surrounding region, is bigger than ever. Exhibitions from more than 60 participating venues are included, and the biennial’s artistic director and curator, Kevin Moore, has contributed eight more of his own. So it might be forgiven if not every last one of the thousands of images presented quite fit the biennial’s theme, “the Undocument,” which is meant to explore, according to biennial literature, “alternative understandings of the documentary photograph—its claims to objective realism and simultaneous potential for pure fantasy.” While some of the photographers included in the biennial, including Bernd and Hilla Becher and Frank Gohlke, do, indeed, represent the more clinical side of the documentary spectrum, more often than not, the photographic smorgasbord delivers on its promise. The result is a rich, if sometimes overwhelming, tapestry of lens-based media—diverse, enticing and, fortunately, rarely ever what it seems to be at first glance.

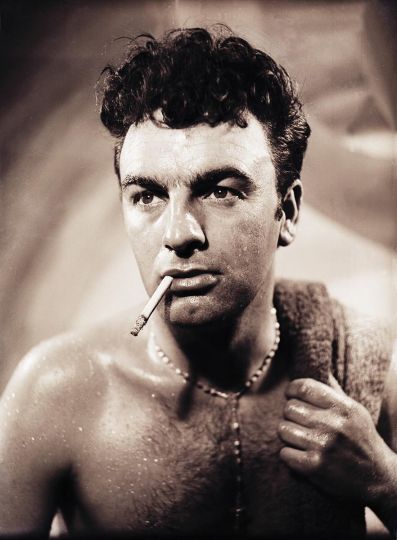

South African artist and activist Zanele Muholi gained worldwide acclaim for Faces and Phases, an expansive portrait series of fellow members of her country’s LGBTI communities. But it is a more recent, and more personal, work, also on display in the exhibit curated by Moore, Personae, at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, that best engages the question of photographic distortion. This series, Somnyama Ngonyama, on its surface, looks like a series of self-portraits of Muholi. In fact, however, each portrait is as much a projection of the artist as a reflection of those who see her and those who’ve made her. In one image, she wears a homemade ensemble designed to invoke her mother, Bester, who was a domestic worker. In others, using contrast and lighting filters, she exaggerates her skin tone in order to both mirror and interrogate the loaded, everyday lenses through which she’s viewed.

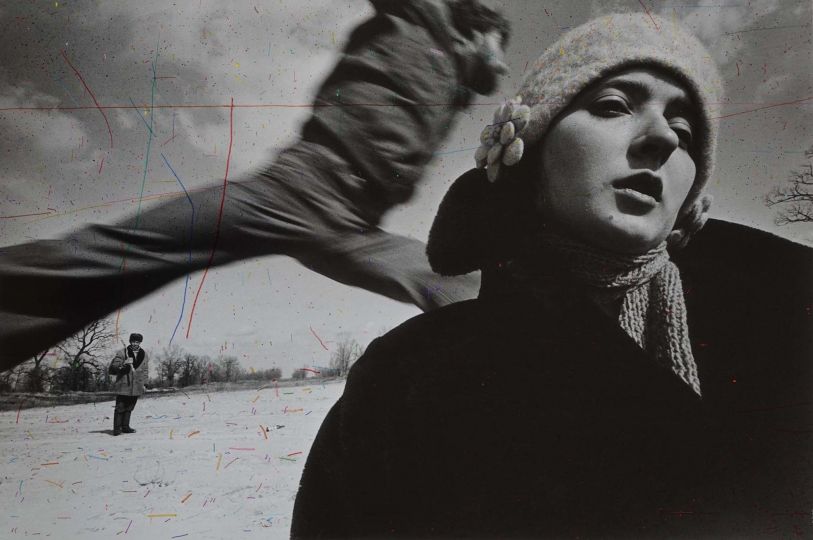

Just down the hall from Muholi’s work, visitors to the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center can see August, an exhibition of Jackie Nickerson’s photographs of African farm workers. The exhibition comprises two series, Farm and Terrain. In the former, in which workers in rural southern Africa face Nickerson’s camera head-on, in a unostentatious pose that will be familiar to followers of contemporary documentary portraiture, Moore perceives Nickerson as “subordinating her role as photographer to their act of self-presentation.” The latter, however, is an overt intervention by Nickerson. In these photographs, the workers’ faces are always obscured by their tools or the fruit of their harvest. While no less a record of real people and places, Nickerson’s device, Moore notes, lends the men and women a “sculptural air while calling attention, metaphorically, to the facelessness of labor.”

Roe Ethridge, more perhaps than any other photographer in the biennial, openly flouts traditional photographic conventions and categories. In Nearest Neighbor, Ethridge’s images have origins that are clearly editorial, commercial or artistic in nature, but, frequently, have been altered or repurposed in a way that changes or complicates their meaning. An image like Louise with House is a good example. Ethridge originally made a photograph of the model and photographer Louise Parker for a magazine, then cut her out of the background, and moved the image in front of a screenshot of a suburban home from Google Street View. The contrasting quality of foreground and background creates an uncanny valley that’s as challenging for the viewer as it is intriguing.

Lest you begin to think that photographs that warp reality are an expressly new phenomenon, take a look at Picturing the West: Master-Works of 19th-Century Landscape Photography at the Taft Museum of Art, which includes early photos that “can be viewed simultaneously as documentary, art, and promotion.” While, indeed, photographers like Frank Jay Haynes and William Henry Jackson presented “natural splendor in a way that was accepted as scientific and factual,” biennial literature notes, “they also constructed a vision of the West as a land ripe for development, exploitation, tourism and, in some cases, preservation.” Rejected photos from the archive of the Farm Security Administration’s documentary program resurfaced by William E. Jones for a video included in the exhibit, New Slideshow, at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center, present a similar puzzle. Permanently damaged with a hole puncher by the notoriously brutal editor Roy Stryker during the mid-20th century, the photos, in this context, dramatically demonstrate the subjectivity behind documentary decision-making.

In an age in which the tools of digital manipulation are easily available and the boundaries of commerce and personal expression are increasingly blurry, it’s likely that the future of photography is with the “undocument” rather than the document. Hopefully, in the years to come, the FotoFocus Biennial will continue to expertly guide us through the complex waters.

Jordan G. Teicher

Jordan G. Teicher is an American journalist and critic based in Brooklyn, New York.

FotoFocus Biennial 2016

The Undocument

Through October 31, 2016

Cincinnati, Ohio

USA