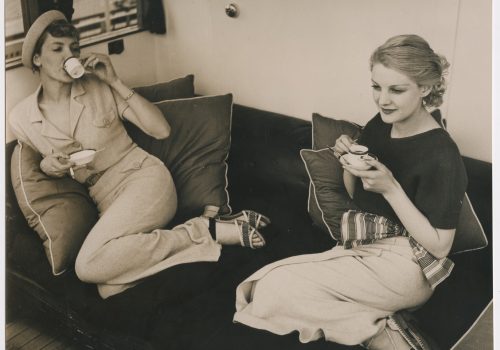

The Musée Nièpce in Chalon-sur-Saône holds an exhibition that looks back at the history of fashion photography in the first half of the twentieth century in France with over 300 works (photographs, magazines, drawings…). The exhibition is accompanied by a book lavishly illustrated.

Like all images, fashion photographs possess their own language. This language is based on a shifting syntax informed by a register of forms, compositions, colors, page layouts and the choice of models. This is also true of women’s fashion magazines which radically evolved in the 1920s, a couple decades after their emergence at the turn of the century.

In these magazines, photographs gradually replaced text, which had in turn given way to drawn illustrations. Originally textual in composition, magazine pages would make room for artists’ colored drawings that slowly invaded the spreads of the Gazette du Bon Ton. Photographers such as Jean Moral, Maurice Tabard, and André Steiner began introducing a “New Vision.” Finally, when Carmel Snow burst onto the scene in 1929, she radically changed the game, and her editorship of Harper’s Bazaar brought a modern woman’s outlook to the magazine.

In their extreme diversity, fashion magazines seem to bring into focus the world of women between 1900 and 1950. And yet, they are but a reflection and a fiction, an illusion of the imaginary world of the modern woman. However, in the mind of the reader, this distorting mirror acquires concrete legitimacy thanks to the illusion of reality. In his essay, “Véracité de l’image” Ludger Schwarte speaks in this context of “images [that] are not only reproductions, mirages, illusions, representations… They present physical elements, they engender worlds. They are no longer merely virtual; they are physically present.”[1]

A certain idea of the woman, conveyed by fashion magazines, procures the illusion of physical presence. This presence is made possible by the very constitution of the image, that is, as a part, but only a part, of the represented “reality.” Such an image, both real and virtual, is as captivating and fascinating as Christian icons, heirs to the Platonic tradition, where eikon does not replace the original, but is a copy participating in it.[2]

The emotional shock generated by fashion magazine photographers was not merely functional, since it affected the construction of individual identity and individual behavior. Advertisement, which saw rapid development in the period, successfully appropriated values heretofore belonging to the domain of religion. These values implied individual conformity, or, in other words, the incapacity to carry out any form of transgression, which would have frustrated the message and endangered the underlying ideological system as a whole. The woman’s image in fashion magazines is in fact a social representation, construction, fiction, that is, it is the image that society wants to project onto itself. A woman must be successful, emancipated, modern, and sensuous. The French woman must embody and glorify a country that helps forge the world’s destiny and that works to conquer, as well as to dominate, the world. This conquest is a form of catharsis not merely in the face of dangers that threaten the nation, but also in the face of centuries of male domination, which, paradoxically, was sapped by the Great War.

Of course, in no way do these photographs represent the real status of the French woman in the first half of the twentieth century. What they do show is not the same as what one could say. Images fascinate, transfix the reader by their formal qualities, by their power of suggestion, and by the fantasies they generate. An anthropological reading of images thus reveals the difficulty involved in their perception and decoding beyond a purely aesthetical approach. Abigail Salomon-Godeau notes in this regard that: “A partly mythic, partly sociological, partly demographic figure that emerged as early as the 1880s, [the woman] was a focus of anxieties and fantasies, a target for advertisers and the entertainment industry, a chip in national political debates, a perceived threat to working men’s interests, the scourge of pro-natalists, the symbol of immorality and sexual license, and inseparable from what Rita Felski has characterized as ‘the contradictory and conflictual impulses shaping the logic—or rather logics—of modern development’.”[3]

The magazine models, seductive and titillating, embodied the ideals of beauty of a dominant social class and of a rapidly growing society that is undergoing a radical transition toward an open, industrial, globalized world; and the mission of these women was to transmit these values, including among the working classes that would assimilate them through osmosis.

The magic created by images makes the conditions of their production no less legible. The world of fashion, the economic context, the personality of the photographers and their models raise questions that go beyond simple aesthetic qualities of the photographs, addressing the tensions between, on the one hand, the real world of creativity and, on the other, the invention of the unreal and of the symbolic. François Laplantine speaks of a knowing gaze, and a critical reading of the virtual world of images encourages precisely such a knowing gaze, so that we can approach the real world in full awareness and with empathy.

William Saadé

William Saadé is a writer and a curator specializing in the arts. He is the artistic director of Palais Lumière in Evian-les-Bains.

Le chic français: Images de femmes 1900–1950

February 10 to May 20, 2018

28 Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

France

[1] Ludger Schwarte,

“Véracité de l’image,” in Thierry Davila and Pierre Sauvanet (eds.), Penser l’art et l’histoire avec Georges Didi-Huberman

(Les presses du réel, 2011),

pp. 223–51.

[2] Suzanne Saïd, “Deux noms de l’image en grec ancien: idole et icône,” Comptes-rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (April–June 1987),

pp. 328–9.

[3] Abigail Solomon-Godeau, “New Women and New Vision: Photography in the Crucible of Modernity,” Jeu de Paume Magazine (October 21, 2015), available at http://lemagazine.jeudepaume.org/2015/10/abigail-solomon-godeau-new-women-and-new-vision-photography-in-the-crucible-of-modernity-en/.