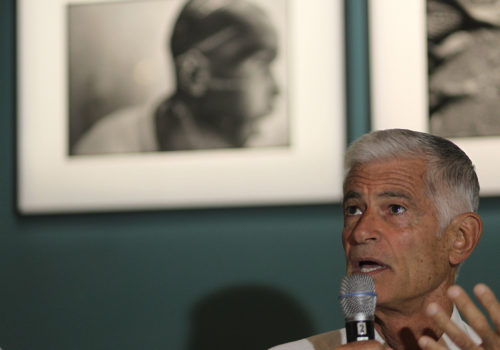

The highlight of the sixth edition of Slovenia Press Photo (SPP) 2015 was the work and life of war photographer James Nachtwey. A project inititated by SPP festival director Matej Leskovsek that finally came to light in the city of Ljubljana this June. The 120 pictures exhibition curated by Alain Mingam at Nina Pirnat-Spahić’s gallery Cankarjevegan Doma was accompanied by an incredibly strong and moving conference. It is rare to hear such generous insight from a photographer on their work. The silence at the end of Mr. Nachtwey’s talk was resonating and humble, a deeply respectful tribute to the American photojournalist. “One of the greatest symbols that persists today in the world of photography and photojournalism” says Alain Mingam, who has been working closely with Mr. Nachtwey for a decade, “the great force of James Nachtwey lies in his framing, profound convictions highlighted in his images…”.

In contrast to his own soft and measured voice, Mr. Nachtwey’s photographs scream, capturing the plight of humans from all corners of the world with a unique visual language full of tenderness and hope. Mr. Nachtwey detaches himself, attempts to be a messenger, to be removed as much as possible, even with the persistent human speculation over the effects of being a war photographer. When asked if faith in humanity was lost after witnessing so much atrocity “All we have are each other. If we lose faith in each other we have nothing”.

There is an endearing, beautiful way in which Alain Mingam represents Mr. Nachtwey. Emotionally attached and moved by the photographs, when asked what it is like working with James Nachtwey, Mr. Mingam describes the photojournalist as a perfectionist, like an artist, every last detail is thought out.

Alain was asked to chose two images and discuss;

A woman mourning at the headstone of a male family member in Kabul.

This image works as a double symbol, a strong image portraying the solidarity within families, as well as the devastating economic effects of losing a male family member – especially in Afghanistan. The terrible solitude of women, amplified by the obilgatory burka she wears, symbolically imprisoning her femininity within the folds of its fabric.

A Hutu man at a Red Cross hospital, his face mutilated by the Hutu ‘Interahamwe’ militia, who suspected him of sympathizing with the Tutsi rebels. 1994, Rwanda.

Winner of the World Press Photo award for Photo of the Year, this image calls out for extreme vigilance in how we read images. The portrait shows a man with a large scar running across his face, easily mistaken for a Tutsi victim of the Hutu vengeance in Rwanda. However, upon reading the caption of the photograph one learns an incredible story; this man is a courageous Hutu who stood up to oppose his tribe’s violence. A strong image with great composition echoing Edvard Munch’s The Scream, this photograph highlights double vigilance in journalism, where the image must always be accompanied by text,

Interview – Maral Deghati/James Nachtwey – June 27, 2015

Is this the first time back to the Balkans since covering the conflicts?

What is it like being here in times of peace?

This is the first time I’ve been back in the region since the wars, and to be here in the context of culture and peace is a revelation. The wars in the Balkans were intensely brutal, barbaric, profoundly tragic. Art and culture are the opposite of war. They are creative, not destructive; they affirm life rather than negating it; they generate light, not darkness. To see such positive energy so beautifully expressed, embraced by a whole community, is a great experience.

Reaching a wide audience through mass media is important for you, can you please tell me about the gallery exhibition approach?

When images reach a mass audience in the same time events are still taking place, they help people relate to what is happening on a human level, beyond ideology, political rhetoric and statistics. Images hold decision-makers accountable for the consequences of their policies. They are a means by which people perceive perspectives and form opinions. When enough people hold similar opinions, ad hoc constituencies are created that begin to exert political pressure. So, the primary venue for my pictures is in mass communication, where images are seen in the context of current events, side-by-side with the work of reporters, explaining the circumstances and complexities of the story and providing historical references.

An exhibition in a gallery or museum is a different kind of dialogue. Images are taken out of the context of the mass media. Rather than being seen as “news” they can be contemplated for meaning that might be more universal, more timeless. A museum show can also serve as a kind of memorial.

Do you have an agent? A photo-editor? With who/how do you work?

Since 1980, when I first became a freelance, I’ve been associated with 3 photography agencies, first with Black Star, at the time run by a wonderful man named Howard Chapnick. He was a true mentor, and he gave me my start. From 1986 to 2000 I was a member of Magnum, and in 2001, I became a co-founder of VII. For the past several years I’ve been working entirely on my own, without an agent, which suits me much better.

For the past 31 years, I’ve had the good fortune to be a contract photographer with TIME Magazine, where I’ve worked closely with a number of great photo editors, each brilliant in their own way. Arnold Drapkin first brought me to TIME in 1984. He was a dynamic, free-wheeling editor when TIME was at its pinnacle in covering news on a weekly basis. He let me run. I took off and never looked back. He was succeeded by Michele Stephenson, who became not only a mentor, but a kind of Guardian Angel. She truly believed in me and would give me the green light even when other editors had doubts. The core of my life’s work was produced when Michele was at the wheel. For the past several years I’ve been working with Kira Pollack, who has done a miraculous job of making a magazine which has less pages, shrinking budgets and a smaller staff, look better than it ever has. Her taste is impeccable. She is a genius at what she does. What they all have in common is a way of leading that inspires. They have the innate ability to bring out the best in whomever they are working with. When a photographer is in the field, often in a difficult, remote, hostile environment, knowing we have the support and encouragement of editors we both trust and admire is an incredibly valuable asset.

You recently published unseen images from your 9/11 archive

What made you do that?

I spent the entire day right in the middle of the chaos and barely managed to survive. That night I made my way to the TIME office, dropped off the film and after the initial edit for a special issue of the magazine, I never looked at it again. My heart had been broken. I had lived through numerous situations that had been equally, if not more dangerous. I had witnessed many tragic events, which had also broken my heart. But what happened in my own city, so suddenly, was a catastrophe of such aggressive force, monumental scale and devastating consequence it was difficult to comprehend what I had just seen with my own eyes, and I understood the world I had known was changed forever.

Ten years went by, and the contact sheets remained in a box. When the tenth anniversary was approaching, Kira and I met to discuss what might be done with the images. She asked me to revisit them and choose some that had never before been seen. But I still did not have the heart to open that box. So I entrusted it to Kira and asked her to make the edit. She called the next morning and told me I better come to the office and have a look.

The issue/ questions around archives is becoming more evident, how do you handle yours?

At this point my career is evenly divided between film and digital. With film we must deal with the physical material of negatives and transparencies. Early on I understood the importance of maintaining my work in a well-organized, archival manner. After some bad experiences I realized the responsibility was too critical to delegate to an agency, so I did it myself. With digital photography the challenge is file management and backup. Like most things in the digital world, it sounds easy, but matters can get very complicated, and it’s easy to make mistakes.

Photographers document history, and it is crucial that images are preserved for the purposes of teaching, for research into contemporary events as well as for historical references and scholarship.

What is it like shooting a situation of conflict in your homeland?

I’d been working in violent, chaotic, life-threatening situations for 20 years, so I knew how to go about it. The grief I experienced for those who had died was no different than the grief I had felt in other places in the world, and I recognized that my feelings for people are not determined by my nationality. I’ve always felt intense anger at the injustices I’ve witnessed. My work has been fueled equally by compassion and rage. But having my society, my home, what I had thought of as my refuge so viciously attacked on such a scale sharpened the quality of the anger.

Your images changed the way a whole generation of photographers cover war, do you see that?

To be honest, I was not aware of that. All I can say is that I’ve been inspired and challenged by the work of my comrades throughout my career, and I continue to be. It’s an amazing community of people, and being associated with my colleagues is one of the things that helps keep me going.

“There’s a vital story that needs to be told…” was your TED wish achieved

For my TED wish I chose to create a public awareness campaign about tuberculosis, highlighting MDR and XDR-TB, two fairly recent mutations of the virus that pose a serious threat, especially in the developing world. TB is one of the most prevalent infectious diseases on the planet, yet it has not been on the radar screen of public consciousness. The idea was that funding for treatment, equipment, training, for research and development happen much more easily when an issue is widely known. The TED network unveiled the project globally on a single day, placing images on giant billboards in public venues, creating guerrilla-style exhibitions, opening a website and online video, helping get the images published in the conventional press, including a sizeable spread in TIME, among other activities. BD, the medical equipment manufacturer, came on board and hosted exhibitions and presentations in several venues globally, including the Capitol Building in Washington. A meeting with members of Congress and their staff, along with notable health care experts was also arranged. I don’t know if the results of the campaign have ever been quantified. I heard directly from a lobbyist for the poor, who had been in the Congressional meeting, that the presentation had been very effective. Other members of the TB community have told me the campaign has helped. To what extent and in what specific ways, I am not certain. The fact is, I never feel I’ve done enough. There always seems to be more I could do. I always think I can do better. I just keep trying.

You said: “difficult to quantify impact of images”, yet today with digital media it is possible to quantify and calculate the impact photojournalism has on a given situation, but don’t you think it has made viewers more passive in reaction (virtual activism has no impact)?

That is the question. What can now be quantified is the number of people who view a picture or a story. What is much more difficult to quantify is what that number means. A number for its own sake might not mean very much. Checking the “like” box might be superficial. Or it might reflect a deeper connection to the subject of the photographs. It’s hard to say. However, if someone takes the time to write a comment the reaction will have been articulated to some degree. What could become effective in terms of creating constituencies that influence change, would be for more people to express their opinions, not about the photography (or not only about the photography), but about the subject. In that way the internet can become a kind of instant letter-writing campaign. Political leaders and policy-makers take note of such things, and they feel the pressure. It would be great if someone who understands the internet developed a way for online photography presentations to become organized to actually have an effect. It does not seem so difficult.