Written by Tetiana Pavlova

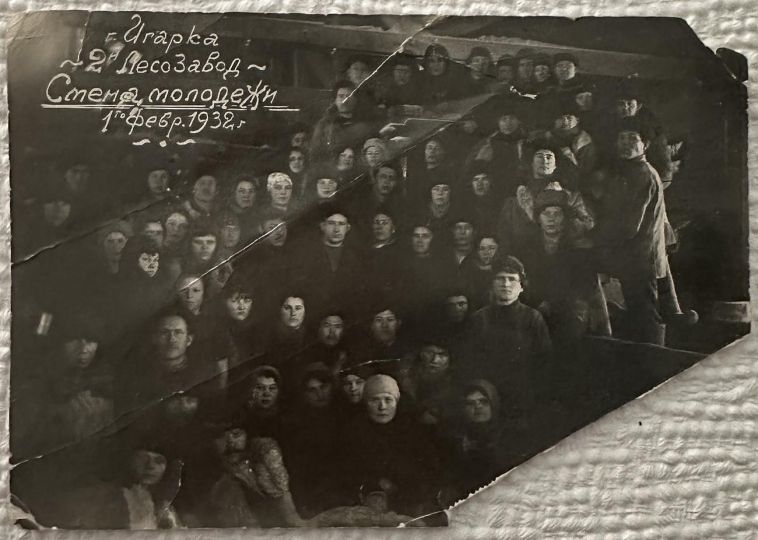

Task force group in the burger mansion of the Kharkiv science (the first public exhibition of the “Vremya” group in Kharkiv, 1983)

For unknown reasons, the mobilizations of the passionate Kharkiv locus precedes the changes in the (Ukrainian) society. The surges in the activity of this seismograph have their own chronology and names. Everyone remembers the Executed Revival of the First Capital (1919-1934), with its avant-garde art and physics, led by the hero of today’s mass media Dau. The period of the 1970s-80s is attributed to the generally accepted trigger of “Kharkiv photography”. At present, we cannot but note the actualization of the phenomenon in a series of expositions (particularly the Grynyov Foundation), which culminated in the work of the PinchukArtCenter curatorial group (B. Geldhof, A. Knock, M. Kiefer) “The Forbidden Image”. This exhibition extensively presented the works of the nonconformist “Vremya” group (1971), whose story is fundamental to the Kharkiv School of Photography (Borys Mykhailov, Oleg Malyovany, Yuri Rupin, Eugene Pavlov, Alexander Suprun, Alexander Sitnichenko, Gennady Tubalev, Anatoly Makienko). And this story has an important checkpoint…

The explosive force, accumulated by the “Vremya” group in the public sphere was first materialized in the “overdue” action in the City House of Scientists in 1983. This was the first legal exhibition of the group, which received a great response. The real assimilation of the phenomenon was just about to begin, despite the fact that a “deaf glory” had accompanied the radical group since its founding in 1971. There were at least three top players, who transmitted information about it beyond the target audience of the photo community: the charismatic Borys Mykhailov and Yuri Rupin, and Oleg Malyovany, who made friends with the artists. It was that exhibition, in the aura of scandal and epatage, that brought the group “Vremya” and its manifesto, the “theory of impact”, into the public space of museum status. But why the House of Scientists? How important was its topic?

The institution, established by the All-Ukrainian Committee for Support of Scientists in 1925, was a legacy of the period when Kharkiv was a capital (1919-1934). With the relocation of the capital to Kyiv, the global scale projections, which continued the innovation pipeline started by the “architecton”1 of Gosprom, were abandoned (Theater of Mass Musical Action by Vesnin Brothers, etc.), many institutions withered away without financial support. But it did not happen to the House of Scientists (KHS), which witnessed the passionate UPhTI story with the legendary Landau. In 1934, the organization was established in the memorial mansion of Academician of Architecture Alexei Beketov (10, Zhen Myronosyts Street). This peculiar building is a tuning fork of eclectic neoclassicism of Kharkiv architecture, with a quotation from the famous Erechtheion portico of Caryatids (later lost) on the facade and a replica of the Baroque plafond (painted by N. Uvarov). Ironically, the putti adorning the faсade, comically shown as “laborers,” actually predicted an era of “sharashka” and “kolhoz “(collective farm), which became the fate of scientific personnel.

The architect Beketov built this burgher mansion with a small garden, representative living rooms and small elegant bedrooms for his family in 1897. The house, with its “dining room” in ornaments and peacocks, in a restrained version of Art Nouveau (painting by M. Pestrikov), has retained an artistic aura, which in a peculiar way responded almost a century later.

However, the idea of an extraordinary exhibition was born in another locus of renewed social infrastructure: in the photo club “Semaphore” at the DK Zheleznodorozhnikov (a monument of constructivist architecture of the 1920s). The methodologist at “Semaphore” was Victor Zilberberg, who later played a significant role in the development of photographic communications in the city. The known today photographers visited the club: Valentina Belousova, Gennady Maslov, Vladimir Ogloblin, Mikhail Pedan and others. Pavlov says, “In 1981, I left my job as cameraman and returned to photography. At that time, having joined the army, and then, having left for Kiev2, I did not lose the need for photo-club life, unlike my friends from the “Vremya” group. Therefore, when Sergei Podkorytov told me about the existence of the “Semaphore”, I immediately responded to the opportunity of turning to such communications. During one of the meetings in the club, V. Ogloblin and I talked about the group “Vremya”, and the problems with its exhibitions. Ogloblin, who stayed permanently enthusiastic about the promotion of photography, came up with the idea of using the new venue, the House of Scientists, and began discussing it with Volodya Bysov who was the leader of the youth section of physicists and had an influence on its exhibition policy. And then, in contacts with Bysov, who was acquainted with Mykhailov, Malyovany and others, the idea of the exhibition of the “Vremya” group was finally developed. ”

In the 1960s, physicists were again given a head start. “We were not afraid of anything then,” recalls Vladimir Bysov. On this wave, under the guidance of an overarching space theme, even abstract paintings were exhibited in the houses of scientists and large research institutes in Moscow. There, in the late 1950s – early 1960s, at the exhibitions brought from Europe and the USA, in the Sokolniki Park, one could see the works of American abstract artists (Gottlieb, Pollock, Rothko, De Kooning), the abstract Parisian school and surrealists (Klein, Soulages, Mathieu, Dubuffet, Magritte, Tanguy). Responses to color fields, tachisme or surrealism, entitled by the name of Salvador Dali, took place all over the world, but on this side of the Iron Curtain, fragmentary information about them was rather obtained from random sources (the “America” magazine, for example). Abstract artists were a favorite target of Soviet caricaturists.

In Kharkov, the field of influence of physicists on “climatic” changes in the Cold War with modernism was not so powerful. However, the high bar set by UPhTI and Landau, despite the repressions, remained. And in the 1960s, we can also see an unexpected alliance of physicists with the surviving avant-garde artists of the 1920s such as Vasily Yermilov, whose disgrace could already be ignored by such luminaries of science as Alexander Usikov3.

The saving alliance, which in the populist interpretation became “a dispute between lyricists and physicists”, was an agreement of experimentalists in science and art. Physicists were given the green light even for the humanitarian sphere struck by Stalin’s purges. And young brothers-physicists Vladimir Bysov and Vladimir Salenkov became new Kultur träger in Kharkov. The mercantile struggle for youth, in which the KHS administration was involved, has also played a role. In 1981, Bysov and Salenkov created the “Pulsar”, Young Scientists’ Club, which was a network of clubs: photographers, theatergoers, poets, bards – analogue of today’s Facebook, – says Bysov.

Despite the “short circuit” that ended the event in Kharkiv in 1983, it fixed a certain point of no return, presenting a renovation project for the entire cultural sphere. It is in this capacity, as the generator of new meanings in a different configuration of artistic communication that photography has acted. Taking into account censorship, the selection of works accepted by the group for the exhibition did not reflect its relevance. At that time, the first “books” by Mikhailov were already created (“Viscosity”, “Crimean Snobbery”, 1982), more and more expanding the area of subjective research of man and society with the introduction of an intimate layer of inscriptions into photography. Considering the huge body of works, which had already been accumulated by the “Vremya” group, one can say that the artworks selected for the exhibition were not too poignant, apart from the exceeding video series of ” superimpositions” in Mikhailov’s slide show and the “dangerous” (according to the organizer of the exhibition V. Bysov) Pavlov’s “Violin”, which within the trigger hippie theme presented new heroes, literally in all their nudity. Nevertheless, asserting its aesthetic platform, the group entered the zone of public conflict, enhancing the positions achieved: the right to individuality, freedom of artistic gesture, interference in the sphere of photographic mimesis. And what was shown?

Photos of Borys Mikhailov, the landscapes of Kharkov, were distinguished by a completely different status of the genre. Shot on color film, they were deprived of the classic values of black and white photography, as well as the “mass culture” of color one. Fresh impressions of the language of color, in which photography started speaking, were deepened by the slide show arranged by Mikhailov, which became the culmination of the event. It was his series of “superimpositions” (or “sandwiches”: slide + slide), which for more than a decade excited the photographic community with extraordinary possibilities of multiple expansion of vision. Overlapping the two slides created paradoxical images, unpacking the subconscious of the stunned viewers.

The exhibition presented works by Alexander Sitnichenko, made in the aesthetics of “straight photography”, which was the equivalent of “truth” for him like unconstrained direct speech. A different type of representation were Gennady Tubalev’s photographs, not devoid of hidden subtexts and ironic codes. There were Alexander Suprun’s old people, far from the stereotypical portraits of “noble old age” (with light on their face and hands). And although Suprun was the most loyal author of the entire group, his works also carried a hidden deformation. The energy of deconstruction, underlying the collage as a technique, is recognized in the “Lilies of the Valley” (“Spring in the Forest”) endowed with a huge suggestion, like a hallucination.

Collage experiments were also presented by the works of Oleg Malyovany: that was an iconic black-and-white series of montages “Gravity” with its surreal apocalyptic connotations. The exhibition featured his color hits and especially the expressive “Fresco”, which was the result of his experiments with color. Mikhailov’s participation in the works as a model adds a certain acuteness not inseparable from his personality affectedness, and it should be noted that his iconography gives a special charm to Kharkiv photography.

The bodily theme, announced at the exhibition in Malyovany’s “Gravity”, and Rupin’s “Night” and “Anxiety”, sounded especially poignant in men’s nudes: in the ten-frame narrative of the Pavlov’s series “Violin” (spring 1972) and the solarized version of the Rupin’s “Bath” (summer 1972), amplified by wide-angle optics (“Horizon” and “Orion”). Although Rupin was annoyed with the camouflage of the overt phallic attributes (with the help of retouching while duping), he was forced to resort to it in order to avoid a ban on the public show of these works. Nevertheless, there was a challenge in the aggressive intonations of male nudity at the exhibition, as if, along with clothing, the repressive rules of Soviet society with its demasculinization and defeminization were rejected. The generation, which in the early 70s desperately chose an alternative freedom, in the 80s ended up: some in the camps (“for parasitism”), some in the grave, some in a madhouse (with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, suicide or “alcoholic mania”).

An extraordinary event in the KHS gathered a huge audience. It became possible in that disintegration of Soviet society that followed the death of another leader. (Although the collapse after Brezhnev’s death was incomparable with the post-Stalin’s one, yet it later led to “perestroika”). At the exhibition, which turned out to be a compromise (and a mistake) in the policy of such a centralized institution as the KHS, photography appeared not as a verifying service, but as a powerful art medium noteworthy of the TATE halls, MoMA in New York and Paris (which was later confirmed by the event expositions of B. Mikhailov). Therefore, it was very important that the in the background of the exhibition there was a cultural location of the museum level. This was the next step after the non-conformist actions of Vagrich Bakhchanyan and street exhibitions in Kharkov in the mid-1960s. In the halo of the public action, the “Vremya” group manifested photography as a new force of influence that could no longer be ignored.

The discussion took place in a conference hall adorned with classic decor, with an absurdly inscribed bas-relief of Lenin into it. On the stage, there were Yuri Rupin, Alexander Suprun, Oleg Malyovany, Anatoly Makienko, Gennady Tubalev, Boris Mikhailov, Alexander Sitnichenko, Evgeny Pavlov. The hall (Beketov’s living room with a grand piano) was packed with spectators, among which were the city’s top artists: Evgeny Dzholos-Soloviev, Vitaly Kulikov, although they did not participate in the debate. And almost in full strength, the next generation of Kharkiv photographers, representatives of the “new wave” 5 was present. The most active speaker in the hall, Gennady Kotovsky, who later became a character in the Limonov’s memoirs, was also captured in the photographs.

Viktor Kochetov’s photo session from the MOKSOP collection is a masterful reportage and a unique collective portrait of the “Vremya” group. A series of photographs with Yuri Rupin, where he symbolically defies the “statue of the commander,” the bas-relief of Lenin on the wall, makes a separate plot. Canonical images with heroes appealing to the portrait or statue of Ilyich (Lenin) usually affirmed the idea of ”dedication to Lenin’s cause, which lives on and triumphs.” The portrait of the “leader”, occupying the center of the wall, also was always central in the paintings and photographs of that time, while in the Kochetov’s photographs, this constellation lost its hierarchical order, violating the laws of Soviet iconography. The dialogue of profiles accentuated the audacity of the moment. But Kochetov with sympathy filmed the hall, which mainly consisted of like-minded people.

And while in the conference hall under the “watchful eye” of Ilyich the “Vremya” group was quite confidently conducting its discourse, in the administration office, a strategic struggle was going on for the “telephone and telegraph”: the director tried to call the KGB. The culprits of the event, the activists of the Young Scientists Club, Vladimir Bysov and the deputy director, saved the situation by snatching the receiver out of the director’s hands. And on the first floor, with partisan speed, someone’s caring hands were taking photographs off the walls and packing them into a car, which had been fetched by a friend. The culmination added a surreal color to the event: the astonished headmistress was brought to the empty walls of the first floor, having demonstrated the absence of a crime. Thus, it made possible to avoid the intervention of the KGB. But the echo of that event for a long time worried the participants, who expected punishments. “Everyone will be punished,” desperately said Rupin then.

This story contains Lotman’s counterpoint of “culture and explosion”. It reads in the limitation of the time available, in the shortness of the event itself, and in assigning the predicate of scandal and epatage to it. The stratagem of intervention on the territory of the House of Scientists contained all the key directions of the non-conformist group: a new poetics of Mykhailov’s social landscapes and his superimpositions, which radically changed the mode of photography and, even wider, art itself; hyperreal collages of Suprun and Malyovany; reality, coarsened by the FDP method in the Makienko’s images; the masculine challenge of the Pavlov’s “Violin” and the Rupin’s “Bath”; the coded irony of the Tubalev’s pictures and the “nudity” of Sitnichenko’s straight photography. By analyzing the exhibition’s composition, it should be noted that the authors realized the deliberately provocative nature of their works, which were a violation of the written and unwritten norms of decency. They carried new criteria for the ridiculous and serious, established a new “repertoire of symbols.” This, of course, was the occupation of the territory. Moreover, could one expect a peaceful resolution of the long-standing conflict, which some authors made public? A scandal, happened at the very center of science and culture, explained the hyperbolic scale, the density of meanings that were important for the general situation in culture and required for the radical changes in a chain reaction of the so-called “perestroika” events. But then, in 1983, it was the first deliberate and articulated manifestation of the strength of real power, which was represented by photography as a new, extremely relevant medium of social and artistic communications. It was the potential, generated by this exhibition that created the subcultural style, which was recognized and recorded in the annals of history as the “Kharkiv School of Photography”.

Tetiana Pavlova

KHARKIV PHOTO FORUM was supported by Ukrainian Culture Foundation