With Foreigner: Migration Into Europe 2015-1016, Daniel Castro Garcia put a face to the individuals caught up in the largest migrant crisis since World War II from a humanist and empathetic stance. His portraits accomplish what photography at its best does: to offer an emotional connection with those depicted, to make us dig and think a little deeper, driving us to explore outside the frame.

On April 2015, two of the deadliest incidents of the so-called European migrant crisis took place in the Mediterranean Sea. In just one week, two overcrowded boats capsized off the coast of Libya, south of the Italian island of Lampedusa, resulting in the death of an estimated 1,200 migrants, a sheer majority of them Africans.

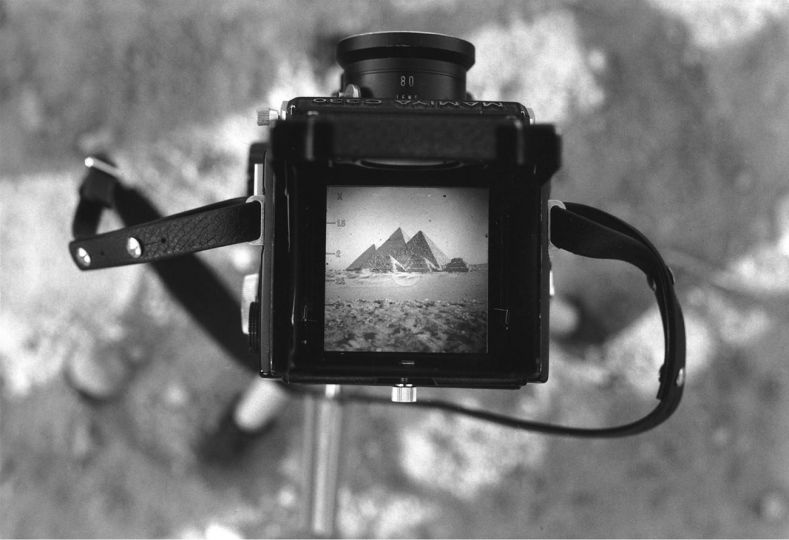

Witnessing those disasters through the media was a catalyst for Daniel Castro Garcia: 3 weeks later, the British photographer and his partner and designer Thomas Saxby (Both born in Oxford in 1985 and professionally known as John Radcliffe Studio) were travelling to Lampedusa with the aim of documenting the situation.

They both had been following the coverage of the migrant crisis through the British press as it unfolded, long before those incidents occurred. How they visually portrayed the migrants, their sensationalist discourse and the vocabulary they used gave them a deep sense of shame and distress.

Because of his familiar circumstances—his parents emigrated from Galicia to the UK for economic reasons in the 1960’s, long before he was born— Castro Garcia is especially sensitive towards migration issues. And though he identifies himself as Galician rather than British or Spanish, he is deeply concerned by the rise of extreme nationalism and separatist movements across Europe, a political phenomenon that has acted as an incentive to carry on with the project as they moved on.

That first trip to Lampedusa was the seed of a much larger project, which has materialized (so far) in Foreigner: Migration Into Europe 2015-2016, a photography book that has recently been awarded with the British Journal of Photography’s International Photography Award. It was also shortlisted in the First Book Award category for both the distinguished Mack Books’ and Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation’s annual contests. Since that first trip, Daniel Castro Garcia, either accompanied by Saxby, who designed the book, or by his producer Jade Morris, visited almost all of the crisis’ hot-spots, only excluding Hungary, Scandinavia and Turkey.

Tell us about the purpose of the project and your way of working.

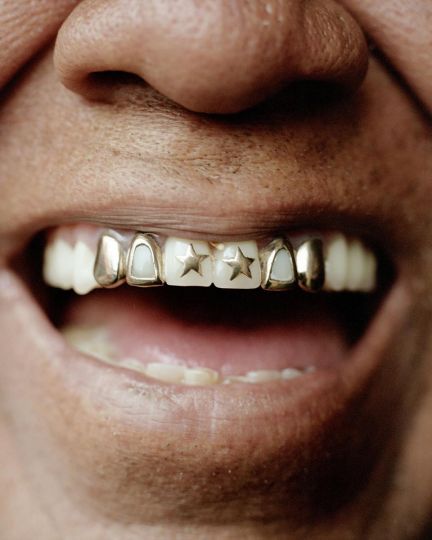

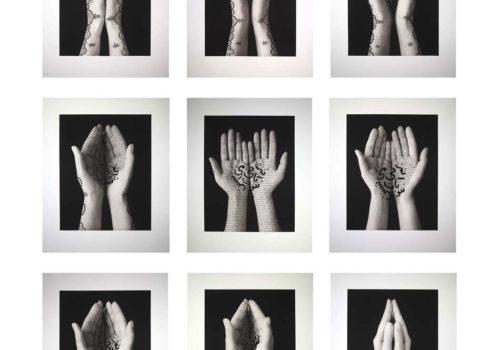

Daniel Castro Garcia: I think that the imagery produced by the mainstream media around this story has been quite voyeuristic. For me, photography represents the opportunity of meeting people, getting to know them face to face and sharing something with them. In fact, I believe that portraits are a collaboration. If the subject doesn’t do his utmost, the resulting photograph lacks that magic component that makes a picture stand out. Besides, I believe that portraits give much more value to the individual stories of these people. Newspapers can offer data, statistics, quotations… but often lack empathy. Our way of working intends to bring a bit of calm. Actually, most of the time, my camera was in my bag. It’s almost as if it’s not about photography, it’s about presenting a work that reflects on how we interact with the situation, to serve an alternative view to visually represent these people in another, more dignified way… and to dignify photography too! My photographic heroes work with a strong concept of dignity. It’s easier to get that dramatic picture of the overcrowded boats arriving at the shore, the migrants fighting with the police or being tear-gassed… It’s much more difficult to try to force the public to rethink their preconceptions and to understand the state of affairs less superficially.

This approach – this calm and dignity that you talk about – are reflected in the pictures, one can feel…

I have to admit that sometimes, especially in the Greek island of Lesbos, where there was such a big crowd of journalists and photographers, I would lose control. I was kind of carried away by the whole chaotic situation, and I found myself acting as if I should get that World Press photo, you know. Nonetheless, I think the images— which are the only ones printed in black and white in the book and that were shot with a digital camera— are pretty good, but have nothing to do with our original approach.

You could have just excluded them from the book, but you didn’t, which is honest of you.

I think this is an essential chapter in the book, since it offers my personal reaction to what I was witnessing. I don’t know if it’s auto-critique, or a way to give the reader the opportunity to contrast them with the rest of the pictures in the book. Yes, I could have suppressed them, but I think it was important. You know, we are saturated with digital images: Instagram, Facebook… anyone is capable of taking good pictures. Maybe it’s like a little commentary about this saturation paradigm also.

You wanted to get the book published before the Brexit vote. Why?

Yes, but we were aware that our influence would be pretty close to zero. Nevertheless, the book (later) has gone much further from what we imagined. The impact on the media has been amazing, a lot of publications which I’m a fan of featured it, and then the prizes, Paris Photo…etc. You see that your work is being accepted on a level you could have hardly imagined.

Since April 2015, I’ve been working on this project 7 days a week, full time, and I’m not overstating it. It has changed my life. I’ve sacrificed the work in my industry (he used to work in the cinema industry as assistant director) and I’m almost penniless right now.

I think the book has succeeded because the project means something also for the people portrayed; I talk with some of them regularly, on a daily basis with 3 of them. We’ve sent part of the money of the prize to some of them who have been stranded in Sicily for 3 years now, who cannot work and have no cash, so they can’t pay the rent, send money to their families, or whatever they need. The book doesn’t even have our name on it, only the studio’s name… I mean I’m grateful for the recognition, but it’s for them that we’ve done it, to represent them in a more dignified way.

Do you think photography should provoke a change on a situation or conflict you can eventually judge as unfair, like the one we’re dealing with here; or do you rather believe it should just limit itself to describe, and in the best scenario, help us understand it and the people involved?

For me photography can rarely be objective. The camera has its limitations. No one except the photographer knows what’s left outside the frame, and therefore the concept of truth is compromised. Despite this, I also think that photography has a brutal power for moving the public—the Aylan Kurdi image as an example. Nowadays, though, amid this visual saturation in which we live, images increasingly struggle to do so. The public gets tired quickly.

As part of the BJP’s prize, you now have a solo show at London’s TJ Boulting gallery, but this doesn’t mean the project is finished yet. What do you have in mind for its second stage?

Well, first of all, we’re currently struggling with the funding. The amount of the prize goes directly to finance the exhibition, which I think gives us the opportunity to present our arguments in a different format and means a step forward for the project.

So we’re exploring ways to raise more money. Even so, we’ve already gone to Lampedusa, Sicily, Rome and Marseille to record some footage that will be included in the exposition. I am editing two short video films, which is really where my audiovisual roots come from.

Later, the idea is to go back to Sicily. I have been granted full access to an unaccompanied minors center, where there are 15 sub-saharan boys, aged 13 to 17 years old. So my plan is to stay there for a long time. If the scope of the first stage of the project has been macro, in terms that it has covered the crisis in almost all of its entire geographical extension, this would be much more micro, much more focused. I would like to consider the position of these children in all this conflict. What are they doing there, without having anything to do? Which opportunities are they being offered, which risks are they facing? How is the system that is taking care of them?

I would also like to keep working with Ali, a guy which I have known since I Peri N’Tera, who is almost like part of my family now, so it starts to become a very long term project. I think that both me and Thomas want to dedicate ourselves to this at least for the next 5 years, or more! It would be incredible to be able to look back and review a really large work on this issue.

Interview by Pol Artola Riera

Pol Artola Riera is a journalist based in Barcelona, Spain. He is @artolariera on Twitter.

Daniel Castro Garcia, Foreigner

March 16 to April 8, 2017

TJ Boulting Gallery

59 Riding House St, Fitzrovia

London W1W 7EG

United Kingdom