Much ink has been spilled over photography, from the moment its invention was announced in 1839 through the latest developments in digital techniques. Until now, a history of this critical activity had yet to be written, and a question needed to be raised: what differentiates photography criticism from art criticism? From Charles Baudelaire to Roland Barthes, to Walter Benjamin and Susan Sontag, Hervé Guibert and Georges Didi-Huberman, this book offers a survey of the multifold debates and discussions provoked by this mode of expression and representation which continues to evolve and question reality.

Social, historical, and technological upheavals in the early 20th century have had significant impact in the sphere of the arts, and marked the experience of the avant-gardes. Dadaism, Futurism, and Surrealism came to reconsider our relation to the world: art could no longer think of itself outside its connections to its time, that is, to objects newly manufactured by industries, to all forms of images, as well as to history in the making and to advances in other branches of the humanities and social sciences.

In a 1923 text entitled “La photographie à l’envers” [“Photography from the Verso”], published in Feuilles libres (no. 30), Tristan Tzara (1896–1963) displayed the extent of his poetic imagination: “When everything that called itself art was stricken with palsy, the photographer switched on his thousand-candle-powered lamp and gradually the light-sensitive paper absorbed the darkness of a few everyday objects. He had discovered what could be done by a pure and sensitive flash of light—a light that was more important than all the constellations arranged for the eye’s pleasure.”[1]

Shying away from lyricism, Philippe Soupault (1897–1990) declared in his preface to a special photography issue of the journal Arts et Métiers graphiques in 1931: “We must place an even greater emphasis on the fact that a photograph is above all a ‘document’ and that it must be considered as such. It may be a motif that will be used in the service of painting or even literature, but it mustn’t be isolated either from its subjects or from its utility.”[2]

This type of approach coincides with the editorial initiatives of André Breton (1896–1966) who illustrated his two masterpieces, Nadja and Mad Love, with photographs by Henri Manuel (1874–1947), André Boiffard (1902–1961), Man Ray (1890–1976), as well as his own. The purpose of the photographs was to dispense with descriptions. We may also invoke the preface to the exhibition catalog of Max Ernst’s (1891–1976) work written by Breton in 1921, which is one of the rare theoretical texts specifically addressing photography, and which was a way for him to promote a utopia of absolute transparency.

Jean-François Chevrier writes in his book Littérature et Photographie: “The Surrealists invented what can be termed ‘the poetic document.’ By linking photography to this definition, they gave photographers new freedom, enabling them both to reject ‘artistic photography’ — inspired by conventional painting — and to relinquish strict professionalism.”

The field of American literature offers some notable examples of this blend of poetry and documentation. Thus the novelist John Dos Passos (1896–1970) inserted into his novel Manhattan Transfer (1925) reproductions of documents about New York, snippets of advertisements, and newspaper cutouts. In the domain of image-driven documentary practice, the James Agee’s (1909–1955) tour de force Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, published in 1936, is accompanied by Walker Evans’s (1903–1975) photographs, which pay tribute to the poor homesteaders fighting for survival.

Documents: a counter-model

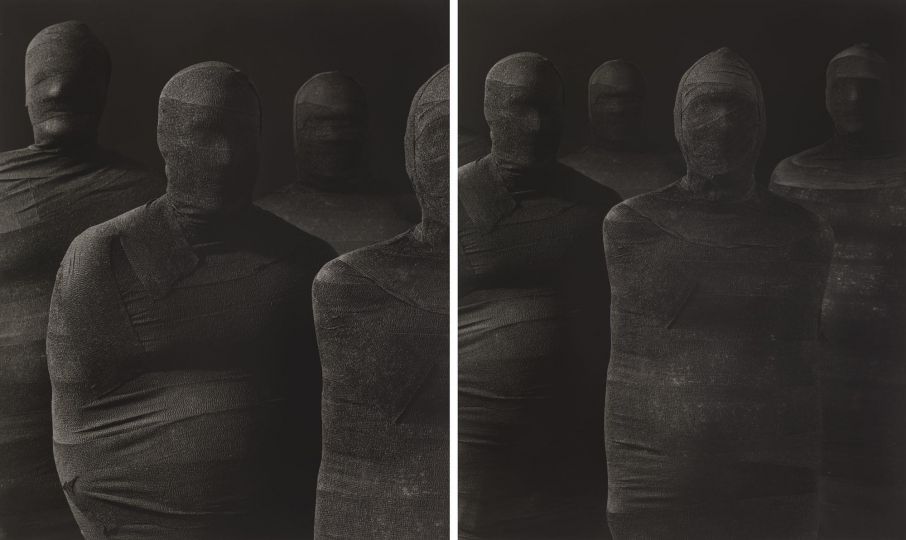

Documents was a scholarly journal, jointly edited by members of the academy, museum curators, and librarians, most notably Georges Bataille (1897–1962), the publication’s “general secretary” who curated the medallion collection at the Bibliothèque Nationale. In a statement of intention introducing the first issue, the editors declared their interest in “doctrines, archeology, fine arts, and ethnography.” Funded by the art dealer Georges Wildenstein (1892–1963), the journal produced fifteen issues over two series, one in 1928, the second two years later. Its most renowned collaborators included, among writers, Michel Leiris (1901–1990), Robert Desnos (1900–1945), and Roger Vitrac (1899–1952), and, in social sciences, Marcel Griaule (1898–1956). Lavishly illustrated, the journal featured engravings as well as photographic creations by André Boiffard, Eli Lotar (1905–1969), and Karl Blossfeldt (1865–1932). The importance accorded to photography, as illustrative images but also in larger portfolios, was affirmed in the collaborative introduction, which further defended the use of images: “Documents wants neither imagination nor possibility. Photography takes the place of dreams.” Even if the relationship between Bataille and André Breton was difficult and fraught with conflict, these choices help to frame the philosopher’s interest in the Surrealist practice of the photographic image and explain why a number of contributors to the Revue Surréaliste[3] left that publication to join Bataille’s journal.

In a text published at the launch of the journal, Michel Leiris affirmed its intentions: “The most irritating works of art, as yet unclassified, and certain incongruous productions, neglected until now, will be the subjects of studies as rigorous, as scientific, as those of archeologists.”[4]

In a recent facsimile edition of the journal, the French poet Bernard Noël insisted in his preface on the importance of opening the doors to a variety of fields of knowledge: “Documents was a vast research enterprise that expanded culture to include folklore, jazz, popular art, and vaudeville. It also drew attention to great ignored artists: Antoine Carron, Hercule Seghers. At the same time it was an enterprise that contested that very culture.” Bernard Noël continued by focusing on the innovative contribution made by the juxtaposition of image and text: “From one issue to the next, Bataille displays. The documents are there, next to the texts, in their vicinity, based on a play between connivance/repulsion, complicity/tragi-comic rejection. Placed next to a text, the image, in its disparity, compels the reader to consider the text also in its image-dimension, that is to say, in terms of montage, margins, characters, etc. Thus the violence of the positioning of text and image works toward producing the desired, anti-idealizing impact on the reader.”[5]

Indeed, on the pages of this journal, which combines doctrinology, archeology, ethnography, and fine arts, one encounters articles on such diverse topics as “A World Tour” and “The Apocalypse of Saint-Sever”; an article on “Human Figures” sits next to another on Jacques-André Boiffard’s “Big Toe,” an image also used to illustrate Breton’s Nadja. In a completely different aesthetic, informed by a more distant documentary perspective, Karl Blossfedt illustrated an article on “The Language of Flowers” with his sculptural views of various plants. In place of the expected scientific name of each plant, the captions hesitate between popular poetry and the view of a gatherer and photographer. Suffice it to judge from the following examples: “Ear of false-rice barley (Hordeum Distichum)” precedes “The tendrils of devil’s turnip (Bryonia Alba). Enlarged 5 times,” or “Azores Campanula (Campanula Vidalii). Enlarged 6 times. The flower petals have been pulled out.”[6]

An important aspect of Georges Bataille’s philosophy concerning the connections between eroticism and the death drive, between Eros and Thanatos, which he began on the pages of the journal and later developed in The Tears of Eros, builds on the importance of an image published in Documents. In 1925, the psychoanalyst Adrien Borel presented the philosopher with a photograph taken in China of the “Torture of the Hundred Pieces,” inflicted on Fu Zhu Li. Bataille admitted in his essay, “This photograph had a decisive role in my life. I have never stopped being obsessed by this image of pain, at once ecstatic (?) and intolerable.”[7] He elaborated on the particular quality of this contradictory moment: “[But only an interminable detour allows us] to reach that instant where the contraries seem visibly conjoined, where the religious horror disclosed in sacrifice becomes linked to the abyss of eroticism, to the last shuddering tears that eroticism can alone illuminate.”[8]

Such is the diverse field of research opened up by the journal edited by Bataille. Within this unusual editorial space, he undertook to dismantle, by means of theory, the notion of resemblance and to operate a figurative montage by establishing new relationships between text and image. Georges Didi-Huberman studied the innovative character of this enterprise in La Ressemblance informe (1995): “However, what remains fascinating, in the issues raised by Documents, is that the possibility of manipulating images seems to lend this ‘knowledge through coming into contact’ — contact not only between objects, but also between heterogeneous fields of knowledge — a resolutely concrete character.”[9]

Christian Gattinoni

Christian Gattinoni has taught at the École National Supérieure de la Photographie in Arles since 1989. A practitioner of writing and photography since the mid-1970s, he has carried out a cycle of images on the memory of the history of the 20th-century through an homage to his father as belonging to the second generation. He splits his time between art criticism, exhibition curating, and image pedagogy.

Yannick Vigouroux

Yannick Vigouroux is a graduate of the National School of Photography in Arles. He is an art critic, curator and photographer. In the same collection he published, with Christian Gattinoni, Contemporary Photography (2009), Early Photography (2012) and Modern Photography (2013).

If you have missed the first episode dedicated to this book, click here.

Histoire de la critique photographique

Published by Éditions Scala

€15.50

[1] Tristan Tzara, “Photography from the Verso,” quoted in Walter Benjamin, “Little History of Photography,” trans. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter, in Selected Writings. Volume 2: 1931–1934, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 2002), p. 523. Walter Benjamin gives 1922 as the date of the article. — Translator’s note.

[2] Philippe Soupault, “État de la Photographie,” in Arts et Métiers Graphiques: Photographie (1931), translated as “The Present State of Photography,” in Photography in the Modern Era: European Documents and Critical Writings, 1913–1941, ed. Christopher Phillips (New York: Museum of Modern Art/Aperture, 1991), p. 51. Translation amended. — Translator’s note.

[3] The title of the journal in question is Révolution Surréaliste published between 1924 and 1929. — Translator’s note.

[4] Michel Leiris, “De Bataille l’impossible à l’impossible ‘Documents’,” in Critique: Special Issue, Hommage à Georges Bataille, vol. 19, nos. 195–6 (August–September 1963), pp. 685–93, translated in Brisées: Broken Branches, trans. Lydia Davis (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1989), p. 242. — Translator’s note.

[5] See Georges Batailles, Documents, ed. Bernard Noël (Paris: Mercure de France, 1968). This volume brings together all of Bataille’s contributions to the journal. A complete facsimile of Documents was published in 1991 by Jean Michel Place, in collaboration with the journal Gradiva, and prefaced by Denis Hollier. — Translator’s note.

[6] For the sake of completeness, the Latin names included in Documents were restored by the translator. The vernacular names have been translated literally. Their English equivalents are, respectively, two-rowed barley, mandrake, and Azorina. — Translator’s note.

[7] Georges Bataille, “Chinese Torture,” in The Tears of Eros, trans. Peter Conor (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1989), p. 206. — Translator’s note.

[8] Ibid., p. 207. — Translator’s note.

[9] Georges Didi-Huberman, La Ressemblance informe, ou le Gai Savoir visuel selon Georges Bataille (Paris: Macula, 1995), p. 39. — Translator’s note.