He was one of the most vehement ludions of this young French photography which was created in the middle of the Seventies, an amazing publisher and a very great seducer!

The Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie in Arles was a sort of unavoidable pilgrimage, a Cannes Film Festival without starlets and stars. We never got bored at night in the Place du Forum drinking pastis and beers under the statue of good Frederic Mistral who never said a word, but like all festival-goers looked at the photos, which were projected on a white canvas screen. But when hordes of gypsies and gauchos burst out unexpectedly on the parigot (parisien), it became really more exciting. Tables and chairs flew in the air, everyone ran off without paying for their drinks under the insults that sounded like grenades, treating some gangs of little fags and inviting the other assholes to fight. But Arles was nothing without the ritual of reading portfolios that allowed young photographers to show their prints preciously presented in cardboard boxes in front of the professional dignitaries who held meetings at the hotel d’Arlatan in the salons or outside but always under the eyes of a crowd who had come expressly to listen to the critics and the advice of the masters.

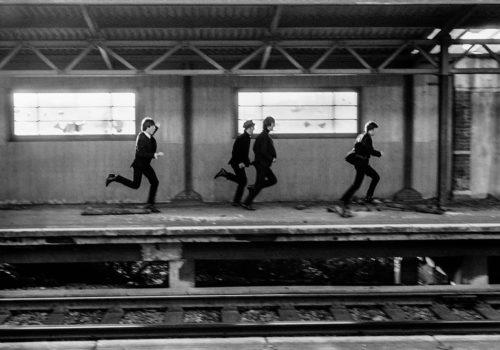

1975 was a pivotal year for photography in France, of which Arles unintentionally served as a sounding board. The young Americans came en masse and they ran after the famous photographers and especially behind the curator of the National Library, Jean-Claude Lemagny, to show him their works and eventually to enter the honorable institution. “I want to show you my latest work” became the tune of the summer, taken in chorus by all those who found the American presence a little too important. But at the time, all that was new came from the USA: the magazine Rolling Stone, the music but especially the pictures of a country in crisis and disenchanted with such as Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand or Lee Friedlander. Ralph Gibson was present in Arles to project the images of his finally completed trilogy Days at sea, black and white photographs which face to face created mysterious reports, invented metaphors, gave birth to mental images coming from the unconscious

Leaving the Forum Hotel, I literally fell on Caroline and immediately fell in love with her. I loved her white dress, her dark skin, her thick, curly hair, her lifted nose, her Italian look. I had invited her to visit the exhibitions, to guide her, with this idiotic thought that I would arouse envy and jealousy among my photographers buddies. Eugene Smith seemed to me too fastidious with his terrible images of fishermen victims of mercury in the village of Minamata in Japan and I found Eva Rubinstein boring with her ecumenical nudes. But I was seduced by this damn’ Charles Harbutt who stripped down urban America and Michel Saint Jean who tore a piece of the lie of the dream of Quebec. André Kertész, a Hungarian emigrant, made a great impression on us, especially because of the many modern ways his photographs opened, his rigorous framing which he made even more daring with the little Leica that he was the first to handle with dexterity, and always this huge sensual appetite for life that he devoured with humor.

In the evening, my friend Patrick Chapuis, who had introduced me to photography, came to join us in an inn a little out of town and the owner, stocky and full of energy her hands fiddling with her apron, served us some guardian beef and Provencal tomatoes that alone were worth the trip. As night fell, in the open-air amphitheater, the emotion was palpable in the crowd crammed on the tiers. Whispers, little cries, excitement, group of friends who tumbled slightly drunk, hugs and reunions were part of the show. Behind a booth, the Ecoutez Voir team was busy on the slide carousels, setting the last synchronisms trying to ward off the possible multiple accidents that often tainted the different projections. In the front rows, Lucien Clergue embraced Edouard Boubat and the writer Michel Tournier. Anxiously, he banged his watch near his glasses, seeming to fear a technical incident which would delay the projection. The lights were finally extinguished and the stars came out of the sky along with a swarm of mosquitoes that threw themselves first and foremost on the fine and delicate skins. The first part paid tribute to the twenty-six-year-old reporter, Michel Laurent, who died during the last battles of the Vietnam War. We had met at the Gamma agency, exchanged a few words quickly as he was preparing to fly to Addis Ababa. His romantic portrait engraved on his tomb always haunted me when I crossed the Montparnasse cemetery where he rests.

The mosquitoes counter-attacked and a scent of lemongrass invaded the tiers. Caroline had nothing planned to chase them away. Her pretty golden thighs and bare shoulders excited the frenzy of the critters and mine. I gave her my jacket to protect her and my arm tried to calm the heat of the bites with the certainty that she took pleasure in getting closer to me. My mind was lost for a few minutes in visions of extreme gentleness where the caresses on her skin activated my desire. The images on the screen seem distant and fuzzy. At that moment, Lucien Clergue appeared on the stage, crowned by the beam of a spotlight that followed him and announced the next part dedicated to the Viva agency.

Claude Raymond Dityvon, Martine Franck, Herve Gloaguen, Richard Kalvar, Francois Hers and Guy Le Querrec appeared from the public and sided with him. Although they were not the idols of young people, they represented the revival of photojournalism, a way of thinking and living the profession in a different way and, above all, of working in depth and in the long term on social issues outside of the hot news. “I consider that we are mature individuals politically and socially defined. This, coupled with our emotion and our sensitivity, gives us the right to bring our vision of things, “Le Querrec told me in Paris while playing pinball in a bar in the 14th arrondissement. A Breton, as tall as four apples, he had the incredible task to talk in public about Viva, its radicalism in the face of the Magnum agency and the necessary changes in the world of the press. The projection began with very dry but well-paced images through which each of the photographers took a look at the world: exile, the condition of women, the fall of Saigon, the police, the English pubs, the Revolution of the Carnations in Portugal to finish with their joint work Families in France on which they had worked together since 1972.

Then we all met in the square of the Forum as usual to share a last drink and dissect the projection. At a table, Americans were enjoying a bottle of rosé. Ralph Gibson, elegant in a white shirt, long curly hair introduced a very beautiful tanned blonde to André Kertész who, with eyes always alert bowed before her. We sat down next to the Viva gang, disheveled and noisy but happy with themselves. In fact, without knowing it the two schools present that night at two different and yet so close tables were about to shape the creative photography of tomorrow. A photography that finds its place between a frenzied individualism and a concern about the reality that photography reinvented. A place where everyone could find his space or his spaces, here, elsewhere, inside oneself or on the roads of the world.

I allow myself here to make a parenthesis about the Magnum photos agency and the situation of other agencies that over night animated the discussion. The imperator Magnum was in fact a cooperative created in 1947, a kind of absolute reference in the field of photojournalism with a morality, values and a philosophy shared by all its prestigious members: Marc Riboud, Ernst Haas, Inge Morath, David Seymour, George Rodger, Bruno Barbey and the others. United at the same time, this band of idealists set themselves the goal of showing a world in turmoil with carefully composed images that did not accept any reframing by magazines. The agency, a kind of English private club had already written a part of its legend thanks to its founder Robert Capa, lover of pretty women and magnum of champagne and Henri Cartier-Bresson, son of wealthy industrial spinners from the North of France. The latter, a virtuoso of the 24×36, frustrated with painting, in a fleeting moment and suddenly succeeded in absorbing the world in his viewfinder, ordering the various elements that composed it with the precision and concentration of a Zen practicing archer. Cartier, as we all nicknamed him in the trade, remained a living legend and his images through exhibitions and books always inspired enormous respect.

However, his intransigence, his lesson-giving side were seriously starting to annoy the young reporters. His decisive moment, which often reduced life to a setting in front of which we just skipped in front of the events annoyed everyone who saw in photography a total commitment, an implication in the daily life of the people. However Magnum made us dream, and exacerbated the jealousy and if the cooperative was openly criticized, privately one caressed the dream of becoming a member. If the agency was running out of steam, demanding a new healthy breath, it would soon have fresh flesh to put in its mouth.

Beside it, a string of news agencies, Sygma, Sipa, Gamma recently formed to meet the demands of the increasingly crazy news, threw young thieves thirsty for adventure on the roads of despair, into the fangs of history, in the heart of volcanoes lit by dictatorships and genocides, in the unbearable scents of burning flesh. They armed themselves with brand-new Nikon or Canon cameras in shock to quickly bring back wide angle photographs, encompassing at once the protagonists in the foreground screaming their suffering or revolt and behind them the theater of operations.

Then, Viva came in 1972, a little in reaction to Magnum and the press photo as it was practiced, manipulated and usually conveyed by the press and many traditional media. A cooperative on the Swedish model of Saftra where all members came together to stimulate joint projects, create a real emulation, warm up the heart around cigs and glasses of wine to remake the world in every way. It was during this memorable evening that Guy Le Querrec told me that he was going to join the Magnum agency with Richard Kalvar, thus initiating a definitive break that would precipitate the closure and the ideals of Viva, leaving Claude Dityvon in the street, alone, worn out and tired of fighting.

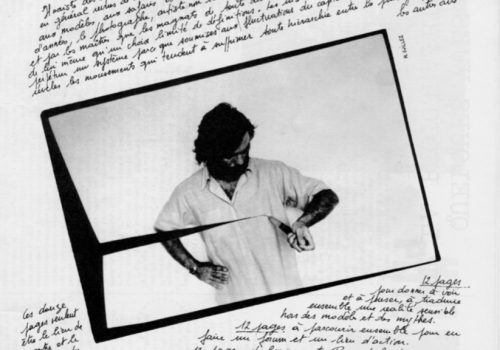

It is no coincidence that we decided to publish and distribute the first issue of our newspaper during these Rencontres. Sixteen pages in black and white, that we hand folded, texts typed with a typewriter in urgency and passion. As we hoped it created an event, not that it was insulting or provocative but because it served as a detonator. Let us be clear, the festival itself was not in question especially that year, the programming was of good quality but Lucien Clergue and the founders did not realise the exasperation of the young photographers who felt excluded at the expense of the great masters or the Americans. Thus, in the courtyard of the Hôtel d’Arlatan, a lively quarrel pitted the revolutionary poet André Laude against Jean-Philippe Charbonnier, a famous brave photographer and husband of Agathe Gaillard, which degenerated so much that the debate intensified outside, in the seminars and succeeded in gaining other interlocutors.

The journal Contrejour opened a debate and a salutary reflection on the current photography in France, its place in the society by highlighting that it existed well beyond a generational problem, a contempt of the institutions and the system as to its emancipation and its diffusion. Many young photography enthusiasts, journalists and even some officials with progressive ideas defended Contrejour by asking that the festival in the future be more open to another form of photography, to newer forms of reportages, to experiments with the photographic practice itself crossed by the other arts. In short, the two thousand copies were all gone quickly, leaving us to consider the release of another issue after the holidays.

The mosquitoes seemed to pause, probably because of the rising wind. The punctum so dear to Roland Barthes was now irresistibly embodied in this knee discovered by my side, I could not hold my hand. Arles and this beautiful summer!