In her book, Une histoire contrariée: Le musée de photographie en France (1839–1945), the historian Éléonore Challine retraces the slow and difficult process to legitimise photography within the French institutional sphere. This is a history driven by individual personalities convinced of the need to preserve photography and give it a museum. Structured as an extensive and thorough investigation, scouring archives and unpublished written and visual traces of these projects, Challine’s study unfolds like a bourgeois drama in five acts. The Eye of Photography presents an extract—the last in a series of three—entitled “The equivocating collector.”

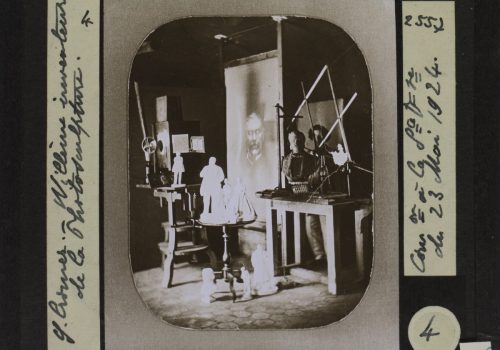

All museums, regardless of their type, started out in the same way. An original collection, assembled by private initiative, constitutes the germinal contribution, which grows over time to include new additions thanks to legacies and donations of other collections. Starting a museum of photography was neither a difficult nor a lengthy process. It existed as a potentiality. A portion of the museum’s treasures, that is the treasures from a unique collection in the world, Mr. Cromer’s, had already furnished, under the heading “Rétrospective Nièpce–Daguerre,” a temporary museum at the Photography Exhibition at the Palais de la Porte de Versailles in 1933.[1]

Many thought that the Cromer collection would easily become public at a time marked by an increase in donations and bequests to the State. Admittedly, since the late nineteenth century, collecting had been reported to be among “the most notorious phenomena of modernity, associated with a boom in trinkets, the expansion of the art market, and the multiplication of museums.”[2] Walter Benjamin even saw the practice of private collecting as a major social and cultural phenomenon in the nineteenth century and, needless to add, in the early twentieth century. Private collecting had left a mark on the public sphere of museums. In fact, starting in 1900, the rise in donations and legacies complemented the policies implemented under the Third Republic, fostering the creation of museums in the name of national greatness and international influence of France.[3] However, how did the passage from a private collection to a public collection take place? Donation was one of the main legal instruments of this transition, amounting to the acknowledgment of the taste of the collectors. Yet it is exactly this process that failed in the case of the Cromer collection, which in terms of photography was by far ahead of any public collection.

On two occasions Cromer openly offered his collection to the State.[4] In 1925, he declared his readiness to “relinquish” it: “The day our project has been accomplished, at least to a sufficient degree, we will be ready to relinquish our own collection to a new enterprise, under certain conditions of purely moral nature.”[5] He required that one of the exhibition rooms be named after his younger half-brother who had died for France and that he himself be authorized to continue looking after the collection and expanding it “as if it were still ours.” Cromer had a hard time seeing his dispossession through to the end. One way or another, he would remain the guardian of his collection for life. As a result, his proposals were always ambivalent.

The second time Cromer sought to convince the State of the singular value of his collection was in 1931. This time, it was no longer a question of donation. Facing the financial and stock-market crisis that ruined his income, Cromer wanted to trade his collection for a pension. He therefore offered to cede the collection to the State and install, classify, and catalog it for 24,000 francs a year. He calculated that this pension would cost the State Treasury no more than 320,000 francs (or thirteen years’ worth of revenue). He added that the sum was lower than either the offers he had received from abroad or the total cost involved in assembling the collection. The collector raised new demands:

“Moreover, this collection should, among other conditions, be preserved (partly accessible to the public, partly in storage) in adequate and secure locations; it should be maintained as a whole, named after me, and no element should ever be removed; no part of the collection should ever be loaned, even on temporary basis.”[6]

Like many collectors, Cromer was anxious about the dispersion of a collection he had conceived as an organic whole. The reaction of the Directorate of the Beaux-Arts[7] to his letter is not known—the silence of the archives is sometimes telling.[8] After Cromer’s death, the question was raised anew:

“Now that the future curator of the Museum of Photography, as he was often called, has left us, we are confronted with a major question. What will happen to the collections, which France, the Mother of photography, should perforce adopt as an integral part of her heritage? Will they be dispersed? Will they go abroad? Foreigners ardently coveting them are legion.”[9]

Dialog of the deaf

As confirmed by the archives, the Directorate of the Beaux-Arts presented a timid offer of purchase. The day after the death of the collector, the director of [the graphic arts magazine] Arts et Métiers Graphiques, Charles Peignot, was sent to scout the situation. He wrote the following letter to Cromer’s widow:

“I have only had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Cromer once, when he was kind enough to see me and let me view his admirable photography collection. On that occasion, Mr. Cromer confessed he found it regrettable that there was no Museum of Photography in France to which he could bequeath it. I am not apprised of your plans, nor do I know whether Mr. Cromer communicated his wishes in the matter. I have taken the liberty of writing to you because I am able to tell you that a project is currently under review, which, if carried out, would most certainly satisfy the desire expressed by Mr. Cromer. I would love to meet with you and learn more about your intentions.”

Not holding any official position at the Directorate of the Beaux-Arts, Peignot was one of the emissaries chosen to open negotiations with Mrs. Cromer. Two weeks later, in January 1935, Peignot renewed his offensive in a letter in which he specified that it was the Director-general of Beaux-Arts himself, Georges Huisman, who had entrusted him with this mission.[10] A meeting was literally forced upon the widow the following Saturday. It was an utter fiasco. Here is Marie Cromer’s own version, scribbled on the front and back of Peignot’s letter:

“Three people paid me a visit in Clamart (arriving an hour late). The day being set aside for the cemetery, I had to make them understand that I had no time, not wishing to miss my cemetery visit. […] These three people wanted to reap whatever benefits they could from the collection.”

The visitors included, of course, Charles Peignot, as well as Laure Albin Guillot, a photographer and head of the art and history archives of the Beaux-Arts since 1932. We do not know who the third person was. Mrs. Cromer wrote further in the same letter: “Mrs. Albin Guillot spoke to me in a language insisting that it was my duty as a Frenchwoman to bequeath to the State, pure and simple, the collection assembled by my late husband between 1903 and 1934.”

For the Cromer widow it was now out of question to make a bequest of her husband’s collection. She personally went to Rue de Valois where she met with Edmond Labbé, the curator-general of the 1937 International Exhibition, and with Huisman himself. The exact date of that meeting is unknown, but it was likely sometime in late 1938 or early 1939, as she was negotiating with Kodak, still hesitant to sell the collection. The response she was given was final, as she jotted down on the back of Peignot’s letter: “They made it clear that big events were impending and that there was nothing the State could do. […] The war is imminent, it’s no time to be thinking about a museum!” If the French government made any kind of offer with a view to acquiring the collection, she must have considered it to be too low: the French administration may have offered 300,000 francs, while the widow expected 700,000.[11] The collection was thus offered to the highest bidder.

Éléonore Challine

Born in 1983, agrégée in history and a graduate of the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, Éléonore Challine is a lecturer in history of photography at Université Paris 1—Panthéon-Sorbonne. Une histoire contrariée: Le muse de photographie en France (1839–1945) is her first book.

Éléonore Challine, Une histoire contrariée. Le musée de photographie en France (1839–1945)

Published by Éditions Macula

€33

http://www.editionsmacula.com/

[1] Pierre Liercourt, “Le futur musée de la photographie,” Photo-Illustration, no. 6 (August 15, 1934), pp. 9–10.

[2] Véronique Long, Mécènes des deux mondes, Les collectionneurs donateurs du Louvre et de l’Art Institute de Chicago, 1879–1940 (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2007), p. 10.

[3] Ibid., pp. 180–181.

[4] As of 1918, Cromer proactively called for the establishment of a National Photography Workshop: “I have passionately dedicated my life to the study and practice of photography: I will devote without any reservation anything of interest that I have gathered in the course of my career, anything that, through observation and experience, I have learned in terms of creating and organizing workshops and laboratories. […].” Gabriel Cromer, “Le procédé au charbon et les collections de photographies documentaires: un atelier photographique d’État,” unpublished article, May 1918, typescript, BnF, Ad993(9), pp. 7–8.

[5] G. Cromer, “Il faut créer un musée de la photographie. Où doit-il être ? Que doit-il être ? Quelles pourraient être ses premières richesses ?,” Bulletin de la SFP no. 1 (January 1925), p. 18.

[6] G. Cromer, “Proposition au gouvernement d’une collection sur l’histoire de la photographie, de ses précurseurs et de ses applications—11 nov. 1931,” loc. cit. The extant copy of the letter belonged to Cromer and has recently been entered into the archives of the George Eastman Museum. No trace of this letter has been found in the archives of the Directorate general of the Beaux-Arts in the National Archives.

[7] Forerunner of the Ministry of Culture. – Trans.

[8] The extant copy of the letter belonged to Cromer and has recently been entered into the archives of the George Eastman Museum. No trace of this letter has been found in the archives of the Directorate of the Beaux-Arts in the National Archives.

[9] “Gabriel Cromer,” Revue française de photographie et de cinématographie, art. cit.

[10] Letter from Charles Peignot to Mrs. Cromer, January 5, 1935.

[11] Letter from Brigeau, Kodak Pathé, Paris, to J. Pledge, Kodak Limited, Wealdstone (Middlesex), London, July 21, 1938, GEM, box 92.