In the late 1960s, in the early 1970s, there were three very great photographers at the top of the monthly magazine Lui then at its peak: Faroum Gourgouloff, Frank Gitty and Francis Giacobetti. They shared the rubrics of fashion, beauty and above all nudes with the same talent and the same pictorial force! Of course, they represent one and the same person, and this hegemony lasted more than 15 years. Francis Giacobetti is a great photographer and like all the photographers of charm, a crazy lover of the woman. A book published by Assouline this month and a sale at Artcurial in Paris (October 17) put Francis Giacobetti in the spotlight again. We wanted The Eye of Photography to participate as well: our edition today is entirely devoted to him.

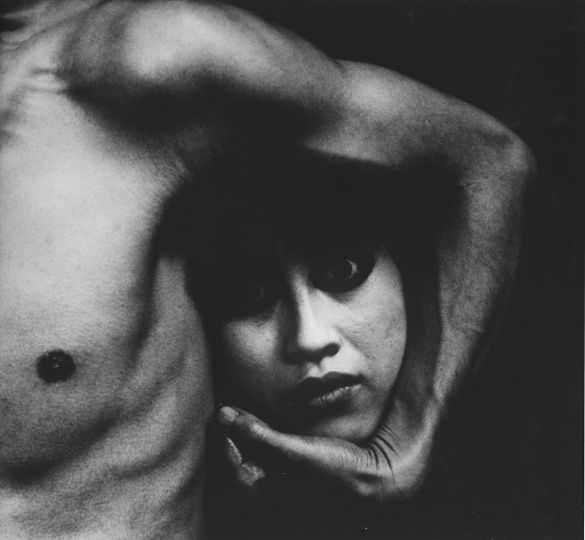

It is just over half a century since a young Francis Giacobetti carved out for himself a unique position in the history of editorial photography. He had tried working as a photo-journalist but was frustrated at not being able to carefully compose, light, and style his images. Turning his back on Paris Match, Francis set out into uncharted territory, collaborating with publisher Daniel Filipacchi on a new magazine for which the young photographer would shape the style and set the tone. The magazine, launched in November 1963, was Lui, a chic, inimitably French riposte to Playboy. Lui rode the wave of the post-war, American-style consumerism that was gaining momentum in Europe with its promotion of a hedonistic promise of material trophies – cars, fancy watches, hi-fi systems, stylish clothes and accessories – and its libertine celebration of beautiful women. The mix was achieved with considerable flair and the magazine became a huge, mainstream success that surely owed everything to Francis’s mastery as a photographer of women. His images gave form to the erotic dreams of a generation – of men and women.

Two years ago, I had spent an afternoon with Francis in his Paris apartment, looking at photographs, talking about photographs, taking stock of what was happening in the world of photography and publishing, reflecting also on the shifting sands of fashion and the reality that a young generation knew little or nothing of his career. The following day, I went to see an exhibition on Jean-Honoré Fragonard at the Musée du Luxembourg, Fragonard was the defining artist of the age of Louis XV, his images evoking deliciously the privileged lifestyles of the upper echelons of French society, with the rituals or courtship and erotic pleasure central to his imagery. The work was so specific to its time, the perfect mirror of a world of extravagance, sensuality, and artifice that was to end with the French Revolution in 1789. Yet Fragonard’s work has become timeless in its ability to delight, thanks to the great skill and imagination of the artist.

I could not help but reflect on how, despite the two centuries that separate painter and photographer, the paintings of Jean-Honoré Fragonard and the photographs of Francis Giacobetti share these characteristics – of being at once so evocative of a specific social and cultural context, yet worthy of lasting attention by virtue of their exceptional finesse. Time and place as well as artistic intuition and skill served Francis as they had served Fragonard. France in the mid-1960s was heading towards its own upheavals; these exploded in the violent student and worker challenges to the status quo of May 1968. A multi-faceted desire for renewal was in the air; the established order and its values were under threat. Political activism was one face of this seismic shift; a new, sometimes wilfully provocative liberalism was another. This ambiance of revitalisation generated fashions and attitudes to dress and to undress that had a huge impact over the coming years. Francis’s Kodachrome universe of sophisticated carnal celebration in the pages of Lui defined a new mood. It is perhaps no coincidence that within a few short years, bare breasts had become a commonplace on the beaches of the Riviera.

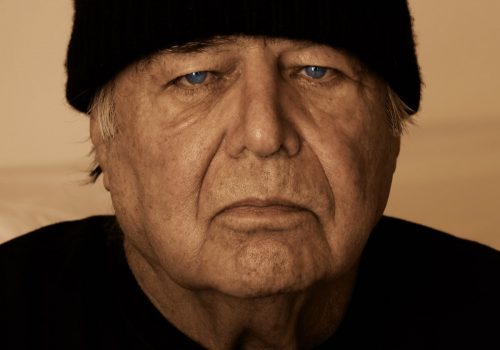

Francis’s range went beyond his nudes. He brought his sensitivity to colour and light and his art director’s rigour to the wider disciplines of fashion and beauty. Nor should we overlook his talent as a portraitist, evidenced in his remarkable portfolio of penetrating studies of some of the most distinguished figures to have shaped our history, and notably in his intimate, insightful series of studies of Francis Bacon.

The world has changed since Francis re-invented and distinguished himself with the celebratory photography of beautiful women. We live in a more puritanical, restrictive, and judgemental climate. Francis himself acknowledges that what seemed so natural and appropriate at the time is seen by many as controversial and unacceptable today, leaving him somewhat bewildered as to the nature of his legacy. As a friend and champion of long standing, I take this opportunity to acknowledge my respect for his talent and creative integrity and my hope that his achievements will earn him the lasting place he deserves in the pantheon of photography.

Philippe Garner

Philippe Garner a travaillé comme directeur du département photographie de Sotheby’s et Christie’s en Angleterre, avant de se prendre sa retraite en 2016.